In the general election, a number of landmarks lead the way to Election Day: the traditional Labor Day kick-off, the ad campaign, September debate negotiations, the debates themselves, and a grueling last ditch effort as the candidates go all out to win over a few more voters in key states. Charges and countercharges fly; excitement builds. While all this is happening, the campaigns are operating with one goal in mind: 270. Two hundred-and-seventy electoral votes is the number needed to win, and major party presidential campaigns deploy their resources accordingly.

Contrasting Visions or Chasing Dollars and

Trivial Pursuit?

Ideally the general election campaign would provide a stage for discussion of the major challenges facing the country and for presentation of competing approaches and ideas for addressing those challenges. The candidates would set out their priorities and give a sense of how they would govern. An effective general election campaign not only gets the candidate elected, but sets him or her on a path to governing.

In reality, however, the fall campaign is

oftentimes not particularly edifying. First of all,

the candidates do spend quite a bit of time

fundraising. Secondly, it is a lot easier to resort to

familiar bromides than to address complicated issues such as

the national debt (+),

entitlement reform or income stagnation. Much

attention in the general election is devoted to defining the

opponent in unfavorable terms. Charges and

countercharges fly. Seemingly trivial episodes,

incidents and gaffes are elevated by the campaigns and the

media, while major issues go unaddressed.

2020 General Election

Campaign

One could argue that President Trump started

running for re-election the day he was inaugurated.

His campaign had the advantage of not having gone through

divisive primaries, while the Democratic challenger Biden

had to retool his campaign from primary to general election

mode. In a real sense, the general election campaign

began once it was clear Biden would be the nominee.

Having garnered enough delegates to secure the nomination,

Biden, as the presumptive nominee, turned his attention to

the goal of obtaining 270 electoral votes in November.

The Democratic campaign added staff and advisors, placed a

few top people at the DNC and built out organizations in key

states. Generally major party nominees move toward the

middle, toning down more extreme elements of their messages,

but Biden did reach out to Sanders. The pandemic

adjusted national conventions in August made the nominations

official, but, by most accounts provided minimal "bounce"

for the respective tickets. The third party and

independent candidates, mostly not well known, appear

unlikely to affect the outcome. In summer some

attention focused on rapper Kanye West, running with backing

from Republicans, but he only managed to get on the ballot

in 12 states.

COVID-19 complicated matters for the Trump

campaign, which was all set to highlight the strong economy;

but instead had to tout the "Great American Comeback."

Republicans portrayed Biden as weak and out of it, a puppet

of the radical left, who was weak on law and order, wanted

to raise taxes and open the borders, and would lead to

socialism. They argued that he had accomplished little

in his 47 years of service. The Trump campaign and its

allies also sought to tar Biden with scandal by making a

major issue of Hunter Biden (1,

2,

3,

4);

the tack seemed ineffective in view of the major issues

facing the country.

The pandemic helped Biden by enabling him to

keep a low profile, participate in carefully orchestrated

events, and avoid gaffes. Biden's main theme was the

need to "Build Back Better;" he also continued his message

that the soul of America was at stake in this

election. Experience and empathy were key parts of

Biden's appeal. Biden and the Democrats focused

heavily on arguments that Trump had botched the response to

the pandemic, costing thousands of lives.

Biden consistently led in national polls, and

through October poll after poll from battleground states

showed Biden ahead, sometimes within the margin of error but

consistently ahead. However, the presidential race is

effectively a series of state based campaigns. Whereas

in 2016 late deciding voters tipped the race to Trump, in

2020 the pool of persuadable voters was quite small.

Still there remained the possibility that the polls were

missing "shy Trump voters." The Trump campaign

expressed confidence in its internal polling and emphasized

that it had many pathways to 270. Indeed in a Sept. 8

conference call the campaign presented seven different

scenarios to achieve 270. In particular, the Trump

campaign hoped to replicate the formula which helped it pull

upsets in states such as Wisconsin and Pennsylvania in 2016:

win the vast majority of the smallest (population) counties.

Trump campaign kept up a very active schedule of campaign travel by the principals and surrogates, including airport rallies by Trump, Trump family member events, surrogate bus tours, busy field offices and people out knocking on doors. This approach carried risks and drew criticism (+).

The Biden campaign strategy of sticking to

largely virtual events was something of an experiment in

real time and could have been very risky. Rallies,

office openings and other events are the batteries that

energize a campaign. Having volunteers go door to door

and engage voters in face-to-face interactions is proven to

be one of the most effective things a campaign can do.

None of this can be replicated online. Biden himself

led a cloistered existence for the first six months of the

pandemic, consisting largely of virtual events and remarks

read from teleprompters. The campaign adhered to the

virtual approach through September. In September Biden

started to travel more, but doing only tightly controlled

events. Many of these were strange, artificial,

pseudo-events where Biden or the other principals spoke to

small numbers of participants socially distanced in circles

in parking lots. The Democrats also did many drive-in

rallies. In early October the Democrats began some

canvassing in battleground states (>).

The debates were consequential. There were concerns among Democrats about Biden's functioning and how he would perform in unscripted situations such as the presidential debates. In fact however, it was Trump who had a costly debate. His constant interruptions in the first debate may have played well with his base, but did not help him win over other voters. Then the second debate was cancelled. Trump came across as much more measured in the final debate, but by then tens of millions of people had already voted.

Trump did have the power of the

presidency. Policy meshed right in with the

campaign. For example in July the administration

rescinded the Obama administration's Affirmatively

Furthering Fair Housing rule, seeking to appeal to suburban

voters. On Sept. 8 Trump traveled to Jupiter, Florida

to deliver "remarks on environmental accomplishments for the

people of Florida" and he signed a presidential memorandum

protecting offshore areas from oil leasing. On Sept.

13 he signed an executive order "lowering drug prices by

putting America first." On Sept. 15 he presided over

the signing of a peace agreement between Israel and the UAE

at the White House. On Sept.

18 announced billions in aid to Puerto Rico, which he had

earlier opposed. Trump held regular press conferences

during which he could further drive home his message.

At many of his airport rallies, Air Force One, a symbol of

the presidency, was prominent in the background.

There were, inevitably, Trump controversies;

it was almost as if the "chickens were coming home to

roost." For example, September opened with the rumor

that Trump's unannounced visit to Walter Reed Medical Center

in November was due to "mini-strokes." A few days

later the Sept. 3 story in The Atlantic by Jeffrey

Goldberg "Trump: Americans Who Died in War Are 'Losers' and

'Suckers'" generated a lot of controversy. The next

tempest came when excerpts from Bob Woodward's book Rage

indicated that Trump had downplayed the seriousness of the

pandemic. Closing out the month the New York Times

obtained Trump's long-withheld tax returns and on Sept. 27

reported he paid no federal taxes in 11 of 18 years and just

$750 in 2016, while claiming huge losses. Trump

routinely dismissed these reports as "fake news."

Around Labor Day there were reports that the

Trump campaign was running low on money, and that Trump

might even put a significant sum of his own money into the

campaign. The Biden campaign raised a record amounts

and was vastly outspending the Trump campaign on TV

advertising. In a Sept. conference call, Trump

campaign manager Bill Stepien said the campaign's spending

on advertising was "nimble and agile" and also pointed to

the campaign's early investments in the states, something

that could not be duplicated in just eight weeks leading up

to Election Day.

Outside groups worked to influence the outcome. Some of Trump's allies were critical that the pro-Trump super PACs did not do enough. On Aug. 31, Politico reported on a "massive" super PAC effort, Preserve America PAC, led by Chris LaCivita (of Swift Boat Veterans for Truth fame from 2004) and funded by casino magnate Sheldon Adelson and Home Depot co-founder Bernie Marcus. In September former NYC Mayor Mike Bloomberg made it known that he had decided to concentrate his efforts on Florida, planning to spend $100 million to tip the state to Biden. Activity by Republicans opposed to Trump was fascinating to watch and seemingly very effective. The Lincoln Project has led on searing messages portraying Trump as unfit and a danger to our democracy. Defending Democracy Together, led by six prominent conservatives including Bill Kristol, has a number of projects, including Republican Voters Against Trump. There were myriad examples disenchanted former Trump supporters as well as Republicans who served in previous administrations who backed Biden.

In a campaign there is always the possibility

of an October surprise, a late-breaking development that

shakes up the race. For the 2020 campaign, there were

two late developments. The death of Supreme Court

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Sept. 18 came as a

shock. Trump quickly nominated Judge Amy Coney

Barrett. Republicans hoped the nomination would

galvanize supporters (+),

while Democrats emphasized the threat the posed to the

Affordable Care Act if she were confirmed (+).

Hearings started on Oct. 12 and on Oct. 26 the Senate

confirmed Barrett without a single Democratic vote, just

eight days before Election Day. It was a major

conservative win at the cost of a further ratcheting up of

partisan acrimony (+).

President Trump's positive test for COVID at the beginning

of October provided a second big shock. Trump was

potentially at dire risk, and he did spend three days in the

hospital but by Oct. 12 he was back on the campaign trail (+).

Many times throughout the fall campaign

President Trump sought to raise doubts about the integrity

of the election. Hundreds of lawsuits were contested

around the country throughout the summer and fall.

Republicans argued for strict interpretation of election law

in state after state, on everything from drop boxes to

ballot received by deadlines, while Democrats sought to

relax rules on in view of the pandemic. Despite

Biden's consistent lead in polls, the country headed into

November 3 amid uncertainty and worries about possible

unrest.

Record numbers of Americans cast their

ballots before Election Day as COVID prompted a major shift

toward mail (+)

and early in person voting. By Oct. 31, the U.S.

Elections Project reported an astounding 90.4 million people

had already voted.

The pandemic did not disappear. Trump

put a major focus on developing a vaccine through "Operation

Warp Speed." It seemed extremely unlikely that a

vaccine could be developed and introduced before Election

Day, but Trump said repeatedly that a vaccine was very close

(+).

On Sept. 22, 2020, the U.S. hit the milestone of 200,000

lives lost due to COVID-19. In Sept. 26 the U.S. reached

eight million cases, on Oct. 16 eight million cases and on

Oct. 29 nine million. In the week before Election Day,

even as cases reached record levels, Trump maintained the

U.S. was "rounding the corner."

Battleground/Swing States and Other States

A campaign must determine how best to spend

the resources it has available; these include staff,

advertising, and candidate and surrogate visits. In

some states the campaign will "play hard" or even "play very

hard." These contested states receive frequent visits

by the candidate, his or her spouse, the vice presidential

candidate, and surrogates, and the campaign makes serious ad

buys in them. At the other extreme, some states are

essentially written off as unwinnable; they receive minimal

resources. A battleground state is one in which both

campaigns are investing significant resources (staff,

candidate and surrogate visits and advertising). As

noted above, in the Fall the Trump campaign maintained an

active travel schedule; candidates and surrogates, did many

rallies and events in battleground states despite the

pandemic. The Biden campaign did much fewer tightly

constrained pseudo-events with small numbers of

participants.

The list of battleground states can vary

over time and depending upon to whom one is talking.

Recent campaigns have revolved around about nine or ten

battleground states. The 2020 map started with the

closest states from 2016. Trump carried four of the

five closest states, all big ones: Michigan (0.3%),

Wisconsin (1%), Pennsylvania (1.2%) and Florida (1.2%),

while Clinton squeaked out a win in New Hampshire

(0.4%). As the weeks progress, campaigns may upgrade

or downgrade a state's importance as it becomes more or less

competitive. For example, the Trump campaign realized

relatively early on that Colorado was going to be a

difficult state to win; it put little into advertising there

and the Biden campaign followed; from the Biden campaign's

viewpoint it was "safe battleground" state. Virginia

too leaned strongly toward the Democrats while Iowa, Ohio

and Texas leaned to the Republicans. A campaign needs

to have devised several "paths to 270" in the event that

some of its states do not gel as the race draws to a

close. Campaigns look to "expand the map," playing in

states where, if things align properly, a win is

possible. Democrats made serious play in Arizona from

the outset, and in Georgia later on, while Trump made a

major effort to win Minnesota. One can also think of

"expanding the paths to 270." The Biden campaign had a

number of possible paths to victory, while the Trump

campaign had a relatively narrow set of options and could

not open other paths due its more limited resources.

See: Battleground

States

Base Voters, Mobilizable

Voters and Undecided Voters

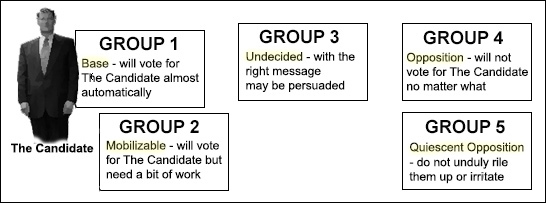

Once a campaign has decided it will contest a particular state, it does not blindly throw resources in. In presidential elections a significant share who turn out will vote for the Republican candidate no matter what and another significant share will vote for the Democrat no matter what. However, while some voters reliably turn out election after election, there are also voters who are clearly partisan in their leanings but do not turn out every election; they need extra motivation and attention. Campaigns have increasingly come to focus on this group, called variously mobilizable, low propensity, low engagement or infrequent voters. Using data and analytics, modeling and micro-targeting, the campaigns can identify these voters and try to motivate them to turn out. Finally, there are the undecided or persuadable voters. The idea is that with the right message the campaign can persuade these voters to support the candidate. Persuadable voters have assumed somewhat mythic status; in Oct. 2012 Slate asked "Dear Undecided Voter: Do You Exist?"

|

|

| For a campaign, the electorate can be

divided into several groups: (1) the base, who

are for the candidate almost automatically; (2)

mobilizable, low propensity or low engagement

voters who need more attention; (3) undecided

voters who can be persuaded by the right

message; (4) the opposition, who will turn out

against the candidate; and (5) the quiescent

opposition, who will turn out against the

candidate if sufficienty riled up. In the

fall, much of the campaign's resources are

directed to groups 2 and 3. Then, in the

closing weeks, the campaign makes a substantial

effort to mobilize its base supporters (group

1). |

Presidential campaigns have grown

increasingly sophisticated. The Obama re-election

campaign in 2011-12 set the standard for a data-driven

campaign; campaign manager Jim Messina placed a major

emphasis on metrics. "This campaign has to be metric

driven. We're going to measure every single thing in

this campaign," he stated in an April 2011 campaign

video. The campaign was constantly modeling and

testing. Will this message work with low engagement

voters? Is this person likely to donate? To

volunteer? The reason for this approach was

simple. Data allows the campaign to use its time and

money more wisely. Although the Trump campaign

in 2016 was not well organized in many aspects, its data and

social media effort proved the key to his success (>).

At

the same time, the experience of the 2016 Clinton campaign

provides a cautionary note on the limitations of data and

analytics. In a Nov. 9 article, The Washington Post's

John Wagner provided an overview of Ada, a computer

algorithm that "was said to play a role in virtually every

strategic decision Clinton aides made" (>).

People in targeted areas and groups can expect to see the

candidates themselves, a lot of political ads and other

campaign communications, and they may find a campaign office

close by. Campaigns also tailor their messages to

specific constituencies through coalition or outreach

efforts, seeking to connect to women, Hispanics, youth and

so forth. Further into the fall newspapers start

making endorsements, and the campaigns make sure to

highlight those.

Campaigns must consider not only where and how but when

they will disburse their resources. Due to increased

early and absentee voting, there is not just one "Election

Day." The beginning of early voting in those states

that have it and, later, the approach of Election Day prompt

the campaigns to redouble their efforts to mobilize

supporters. Phone-banking, precinct-walking, instant

messaging and targeted messages on social media are staples

of get-out-the-vote (GOTV) efforts.

Candidate and Surrogate

Travel

The candidates' time is one of the most

important resources a campaign has. Campaign stops are

scheduled in media markets with high concentrations of

mobilizable or persuadable voters. They range from

rallies, roundtables and speeches to unnanounced or

off-the-record stops. In addition to the candidates

themselves, a wide variety of surrogates trek through,

ranging from family members to political figures to minor

celebrities.

| Aug. | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | By State |

||

| President

Donald J. Trump |

x | >> | ||||

| Vice President Mike Pence | x | >> | ||||

| Former Vice President Joe Biden | ||||||

| Sen. Kamala

Harris |

||||||

| Rationale,

Methodology and Limitations |

map |

In the Fall Democratic presidential campaigns

have traditionally featured a massive ground game with

numerous field offices, field organizers, and volunteer

neighborhood team leaders, which significantly outmatches

the organization on the Republican side. For 2020,

Democrats have radically adjusted that model due to the

pandemic. Meanwhile, the Trump campaign and the RNC

have have built their organization in close cooperation over

about a year and a half, and are achieving record numbers of

voter contacts. Of course, it is not just quantity but

quality that matters, but person-to-person contacts are

effective and it is a truism voters like to be asked for

their vote.

[On a technical note, the field organization

on the ground in a given state is typically carried out by a

coordinated campaign or Victory campaign which is funded by

the state party and the national party and seeks to elect

party officials up and down the ticket].

Much of the money raised by the campaigns

goes into paid media, particularly television

advertising. Traditionally campaigns have put

together ad teams which includes both political and Madison

Avenue talent. (In 2020 the Biden campaign was

distinctive in keeping its paid media operation in

house). Based on polling data, the themes the campaign

wants to stress will have been identified. The ad team

generates ideas to convey those themes, and produces spots

which are then tested in focus groups, and, hopefully,

approved by the campaign management. However, the work

does not stop with an ad "in the can" and approved; careful

planning is required to ensure that the ads are seen by the

target audience. The demographic watching "60 Minutes"

differs markedly from that watching "Judge Judy." It

is left to media planners, juggling GRPs and dayparts, to

put together ad buys. In addition to ads from

campaigns, super PACs and interest groups add their voices

to the mix.

The campaigns are also giving more and more attention and resources to advertising on Facebook and other social media and to online advertising. This can be a very effective way to reach specific demographic groups in specific areas or states, and because it is relatively inexpensive can allow for a more prolonged conversation with the targeted group. As with TV advertising, for online advertising digital ad buyers try to reserve premium spaces such as on popular news sites.

Radio is an effective way to reach some

audiences, for example during drive-time. Because of

its lower profile radio is sometimes used to deliver

negative messages. Persuasion mail and phone calls

also convey the campaigns' negative messages. Magazine

and newspaper

advertising can be very effective, but are not used

much.

See: Ad

Spending in the 2020 Presidential Campaign

While paid media has long drawn attention

because of the amount of resources devoted to it and because

it can be relatively easy to identify ("Paid for by...),

campaigns also strive for earned media and social media

buzz. Earned media means the campaign does an event

that makes the national news or the front page of the

newspaper or is picked up by a blogger. Through his

use of Twitter and the constant controversies surrounding

him, Trump excels in getting earned media.

Social media can be more effective than paid

media. If a friend or acquaintance sends you a message

saying, "Hey, look at this interesting graphic or video from

the X campaign," that is likely to have more impact than a

30-second spot glimpsed on the TV. The campaigns have

staff busy tweeting, posting on Facebook, developing

infographics and sending out emails. In the lead up to

the election campaigns also have volunteers sending out text

messages to people's cell phones. Unlike paid media,

the scope and effectiveness of these efforts is difficult

for outside observers to measure.

Although there is a system of federal funding

for the presidential general election, recent campaigns have

opted to forego federal funds so they can raise and spend

more money. (The general election grant, established

by the Federal Election Campaign Act, comes with a spending

limit; this started out at $20 million in 1974 and has been

adjusted for inflation since). Both the Trump and

Biden campaigns declined the general election grant.

The 2020 race was a record breaker. As

reported by the Center for Responsive Politics, through Nov.

23, Biden for President raised a total of $1.044 billion and

spent $1.043 billion while Donald J. Trump for

President, Inc. raised $774.0 million and spent $778.4

million. In-person fundraising events with well-heeled

donors have been a staple of the fall campaign, but due to

the pandemic the Biden campaign shifted to virtual

fundraisers and still was able to raise record amounts.

In addition to the money raised and

spent by the campaigns, the national parties are allowed to

spend a fixed amount advocating the election of their

nominees (the limit for coordinated party expenditures in

2020 was $26.5 million). The parties are also free to

make independent expenditures supportive of their

nominees.

The campaigns and the parties are not the

only players on the field. Super PACs and other

outside groups spend tens of millions of dollars, mostly

attacking the opposing candidate. According to the Center

for Responsive Politics, through Nov. 9 outside groups

supporting Trump spent $316.7 million led by America First

Action at $149.1 million, while groups supporting Biden

spent $568.5 million led by Future Forward USA at $150.6

million and Priorities USA Action at $137.0 million (>).

It is interesting to consider how this

campaign would have turned out had there not been a

pandemic. So much of the Biden campaign message

focused on Trump's mishandling of the pandemic. At the

same time, the pandemic torpedoed the Trump campaign's

strategy of touting the strong economy. The candidates

and their campaigns responded very differently to the

pandemic. President Trump seemed unable to acknowledge

the loss of life and suffering, while Joe Biden was the

empathy candidate. While Trump and his campaign

flouted social distancing guidelines and recommendations by

holding large rallies, Biden and his campaign responded with

caution, holding contrived events with very limited

access. Pandemic instituted innovations such as drive

in rallies and use of painted circles or hula hoops to

ensure social distancing are not likely to be featured in

future campaigns, but other changes such as more of an

emphasis on virtual fundraising could endure.